Comedians have the ability to be the most important communicators in our society. Why? Because people actually WANT to hear them talk (unlike politicians, environmental activists, and scientists among others). Why is this? It’s not just because “they make us laugh.” It’s also because they are masters of narrative structure as I present here by examining an hour long HBO discussion of four hugely successful comedians. This begs the question, if comics know how to communicate best, why don’t others draw on their talents beyond just laughter?

MASTER COMMUNICATORS. Nobody knows narrative structure better.

HAWKING VERSUS SEINFELD?

Who would you rather listen to for an hour — the late Stephen Hawking or Jerry Seinfeld? How about acclaimed climate scientist Mike Mann or Jerry Seinfeld? How about even entertaining scientist Neil Degrasse Tyson or Jerry Seinfeld? And what about scientist-turned-filmmaker Randy Olson or Jerry Seinfeld?

I promise you the answer for the average American citizen (not American academic) is Seinfeld, Seinfeld, Seinfeld, Seinfeld.

Neil Postman knew this dynamic back in the 1980’s with his landmark book, Amusing Ourselves To Death, whichsmarter people have referenced in recent years (here, here, and here) in relation to the current entertainer/president.

LEARN FROM THE GREATS, EVEN IF THEY OFFEND

The main point of this post is that nobody has deeper “narrative intuition” (the ability to feel, intuitively, narrative structure) than comedians and comic writers. This actually isn’t that big of a surprise if you consider that the ABT Narrative Template came partly from the co-creators of the animated series, “South Park.”

So HBO recorded a discussion in 2012 which drew little attention until recently when it was discovered it had several offensive bits. But if you’re really, really serious about understanding communication then you’ve got to be able to section off the part of your brain that was offended and study this tremendous discussion of four brilliant stand up comics. Just avoid the content around 16 minutes in if you don’t want to hear the worst stuff. You can bet they wouldn’t make those comments today. So skip that part, but learn from the rest.

I’m going to guide you to some of their best comments when it comes to communication.

NARRATIVE SHAPING: COMICS KNOW SHAPE

Here’s the first tremendous thing said. It’s from Jerry Seinfeld around 5:00. He says, “No one is more judged in civilized society than comedians — every 12 seconds you’re judged.”

This is why these folks are so skilled. Being judged that much results in narrative shaping. Comedians are “narratively shaped,” over and over again, night after night. If they bore or confuse they are given immediate feedback. If they feel a joke drag or lose everyone, the next morning they are reshaping it. And mostly through the quickest, most efficient way which is verbally, not written (as we’ve been learning over the past 5 years in our Story Circles Narrative Training program).

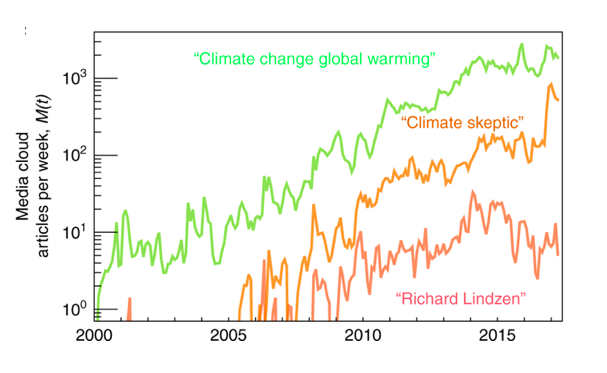

What is the result of all this iteration, night after night, of the narrative structure of comic material? Look at this table from my new book, Narrative Is Everything. What you see is that the best stand-up comics score incredibly high values for the Narrative Index (the BUT/AND ratio). For comparison, few politicians score over 20 and almost none ever score above 30.

What this means is that they are presenting material that is packed with twists, turns and surprises (it’s what the “but’s” provide) — the very material that keeps audiences ENGAGED.

Look at the scores. The most popular comedians are at the top of the heap. At the bottom are a group of much less popular performers, some of whom aren’t even professional comedians. And also, the great Philadelphia Incident of Bill Burr where all he did was hurl insults at the audience, no attempt at telling stories (though if you think about it, his entire “act” was one big contradiction to all the expected norms of a comedian).

STRUCTURE, STRUCTURE, STRUCTURE: FURNITURE AND STEEL WALLS

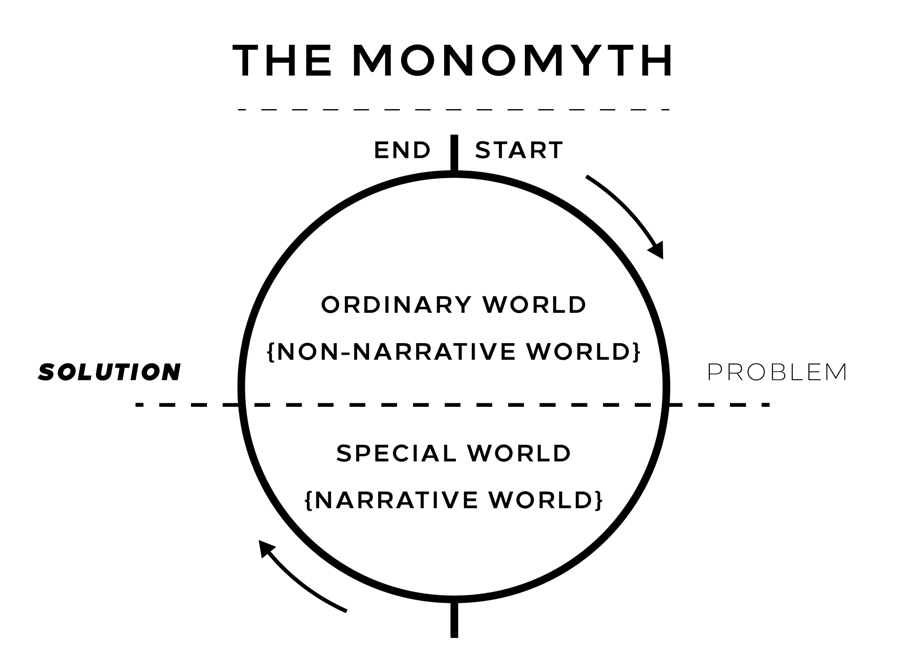

In the discussion Jerry Seinfeld says, “You can put in all kinds of furniture, but you gotta have steel in the walls.” There you have it, in simple language — narrative has to have solid structure. These guys aren’t professors and they don’t think all that analytically, but their entire discussion is all about structure.

It makes me think of three years ago when I asked acclaimed screenwriter Eric Roth, who won the Oscar for “Forest Gump,” how important narrative structure is. He basically said you can get really creative as a screenwriter, but at the end of the day, you still have to respect those basic principles of narrative first noted thousands of years ago by the Greeks.

He is talking about the same thing as the “Christmas Tree” and “ornaments” that Dave Gold uses as the metaphor in his great Politico article in 2017.

NARRATIVE SELECTION: YOU BORE, YOU DIE

Louis C.K. says, “It’s like Darwinists, really, because you have your thing that you do and people flock to it, and if they don’t, you die.” He’s talking about the very concept of “Narrative Selection” that I introduced in my new book. Yes, this is what it’s all about — material gets selected over time. If it’s good, it persists. If it’s boring or confusing it either changes or dies.

It’s not that complicated, as good comedians know.

CONCISION: RICKY GERVAIS IS A MASTER

Ricky Gervais says, “I think of a joke as the minimum amount of words to get to a punch line.” He would know. Watch his brilliant Humanity special on Netflix. He tells about his Twitter wars he engages in. He gets to the point where his punch line is boiled all the way down to just five words, “I should have left it.”

It’s hilarious. He tells about something someone tweeted at him. Then all he has to say is, “I should have left it,” to score the next roar of laughter. That’s what he means by the minimum number of words.

But what’s more important about this is it’s the same thing that Park Howell and I discerned for the ABT — that “the quicker you can get through the A and B, the more we’ll let you have all day with the T.” Exact same thing — Ricky is saying to get through the set up and twist quickly because we’re here for the punch line, which is the THEREFORE.

“THESE YOUNG GUYS” – IT’S JUST LIKE STORY CIRCLES

Chris Rock says, “That’s the problem with these young guys — they think it’s all attitude — but it’s GOT to have jokes under it all.” What he’s talking about is the same thing we’ve seen with Story Circles Narrative Training. Over the course of 5 years we’ve learned that Story Circles is not that useful or rewarding for young, early stage students. They get bored with the repetition element and the simplicity of the ABT template.

As one of the UC Davis 5th year graduate students says in our Bodega Marine Lab video, it’s not until you’ve had some experience with communicating science that you come to realize both how important structure is and how challenging it is. Younger students think the science itself is good enough — just like comics thinking it’s just attitude.

When he says, “it’s GOT to have jokes,” he’s talking about structure — it’s GOT to have structure. Good students eventually figure this out. It only took me about 20 years from when I first heard it in 1989 from the great screenwriting instructor Christopher Keane.

THE NEED FOR “THEME”

The other essential element of story is the need for a central theme or premise. They talk just as much about this. Jerry Seinfeld says, “You gotta have a voice.”

Louis CK points out the essential element of repetition, which is what our Story Circles training is built around. Admiring Chris Rock, he says, “Chris will even keep repeating it if he has a premise. Like women can’t go down in lifestyle. Then he’ll explain it from 50 different angles.”

That is exactly what “messaging” is about. You have a central premise, then you message around it — repeating the basic point from a multitude of angles.

Underscoring how well Chris Rock knows the importance of premise, he says, “A lot of comedians have great jokes, but they’ll be thinking why is this not working? It’s not working because the audience doesn’t understand the premise.”

He adds, “If I set this premise up right, this joke will always work.”

And then Ricky Gervais brings the theme element home by saying, “Really good bits go deep into your head and keep coming back.”

THE GROUP DYNAMIC

Gervais hits on exactly the group element that lies at the heart of Story Circles Narrative Training by saying, “You can’t be the one who decides why you like something.” This is what we constantly tell participants in Story Circles. You can’t sit alone at your desk and write something with perfect narrative structure. As he’s saying, you can’t be the one who decides something is great — it has to be other people. This is really hard to fully appreciate, but is essential in a sometimes anti-social profession like science.

This is such a great discussion. Not just funny. It’s fascinating — four artists, doing their best to be analytical about their craft. It’s packed full of communications wisdom.

BOTTOM LINE: POLITICIANS NEED COMIC WRITERS

I’ve been saying this for a while now. Politicians need comic writers, NOT for their humor (though that’s an added bonus) but because they, more than anyone else, grasp the power, importance and technique of narrative structure.

There is NO REASON for politicians to bore and confuse, as they do endlessly. If you care about your favorite politician, ask him or her if there’s a comic writer in the mix of the speech writing. And I mean a good comic writer — one whose work scores consistently above 30 for the Narrative Index — as is the case with Bill Maher’s writers.

This is the absolute core of effective communication today.