When asked for years for good examples of science communication in film I’ve pointed to HBO Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel. Not that they communicate science, they’re just a model for how science ought to be communicated. This month they brought their excellent narrative skills to the Great Barrier Reef of Australia. In this post I dissect what they presented to show why I think they are so good at narrative. This is how true professionals communicate effectively. I wish more amateur documentary filmmakers and scientists in general would learn from them. More is not more for media when most of it is so poorly crafted for narrative structure (i.e. stop boring the public).

“THE GODFATHER OF CORAL REEFS”! Charlie Veron, one of my old colleagues from way back, sets the world straight on how his own country is killing their greatest natural resource.

THIS IS HOW IT’S DONE PROPERLY

For years I’ve raved about the narrative skills on display when you watch HBO’s Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel. The show has won two Peabody Awards among other accolades. How do they do it?

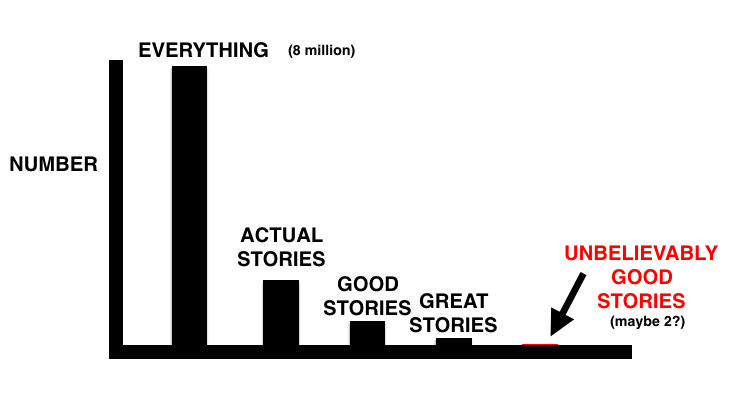

First off, they aren’t driven by any sort of, “You need to know this” agenda. To the contrary. They have a team of people who scour the world for good stories, even if the connection to sports sometimes seems a little stretched. They look far and wide for good stories, first and foremost. Then they work extra hard to shape the narrative structure into as powerful form as possible.

This month they did an excellent segment on the dying of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Without making any specific mention of the amateurishness of most feature environmental documentaries when it comes to narrative, I’ll simply focus on pointing out the various key narrative elements that are so well used in the Real Sports segment.

NARRATIVE MECHANICS AT WORK

Let me start with a few of the key attributes.

THREE ACT STRUCTURE – as we say endlessly in our Story Circles Narrative Training, it’s about the three fundamental forces of narrative. They begin with AGREEMENT. Notice that the first quarter of the show has no tension, no conflict, no issue, no problem — it’s “The Ordinary World” to use Joseph Campbell’s terminology. Bryant Gumbel goes snorkeling on a healthy reef and raves about the beauty.

This makes me think of the summer of 2001 when an editor at the LA Times asked me to write an editorial about coral reefs. She coached me on the structure, saying I should open by “putting us on a coral reef.” This is what the HBO segment does. (btw, that editorial was schedule to run two days after 9/11 occurred — it got booted for obvious reasons, but a year later the editor and I came back with my Shifting Baselines OpEd)

In perfect narrative form, the first act ends with CONTRADICTION — i.e. the statement of the problem. This is exactly what they do, stating the problem which begins the narrative part of their story.

It’s always hard to pinpoint where a third act really begins, but in their story it’s fairly clear as it occurs when they finally move up to “the big fish” that was hinted at from the start (climate change and the coal industry driving it). Bottom line, the structure is excellent.

AROUSE AND FULFILL – it’s the central dictum for mass communication and you see it at work in their three act structure. The entire first act is pure arousal. No information, no statistics, no preachy message — just the pure pleasure of diving on a beautiful coral reef. The narrative process not yet begun — just arousal to start with. The fulfillment will come later, once you really want to know more about this resource.

SUPERLATIVES – superlatives are basically statements of X-tremes (biggest, longest, worst, most dangerous, etc.) and are communications gold in a world of too much noise. The challenge is to not over-reach for them. But if you’ve got ‘em, use ‘em. Which is what they do, being the professionals they are. I count ten superlatives, if we include “Godfather” as a statement of extremes. Of course this is a story that is already set in a world of extremes on the GREAT Barrier Reef, but still, they clearly have the eye for all possible superlatives.

SPECIFICS – rule number one for story is that THE POWER OF STORYTELLING RESTS IN THE SPECIFICS. You see this throughout the piece. Not vague statements about “this is really important,” but specific information and again, statements of extreme, but only where correct and reasonable. Notice that Bryant Gumbel even asks, verbatim, if Dean Miller recalls “any SPECIFIC moment.” This the pathway to the most powerful form of storytelling — to recall individual, specific moments.

DON’T TELL US, SHOW US – twice they yield to this principle — first taking us on a snorkeling trip to a healthy reef, then a few minutes later taking us to dive on a dead reef. It’s the obvious and obligatory footage, but the thing to note is that they weren’t jumping back and forth between the two from the start. No, they took their time giving you a full dose of what a healthy reef looks like. Then they took an equal amount of time to visit the dead reef. These things matter, narratively.

REPETITION – this is the bane of artsy filmmakers who never want to “hit you over the head” with things, or be “too on the nose.” And that’s why they are rarely good at messaging. Effective messaging is all about inculcation — repeating the message, ideally in different ways — but sometimes just bluntly saying the SAME damn thing, as they do a couple of times, especially at the end.

If you’re a fan of John Oliver’s HBO show you may have enjoyed the mission he’s been on showing how the CBS show 60 Minutes egregiously repeats the sound bites of their interview subjects. The host will say, “So that’s what it costs?” The interview subject will say, “So that’s what it costs.” They do it relentlessly. And they are one of the most successful shows in television history. Yes, it’s funny if you look at it analytically, but most of the mass audience isn’t analytical. Which is something that highly educated people have a hard time grasping.

Sorry if you think repetition is tacky. So many of my USC film school classmates headed out in the world wanting to be artsy and not say anything too bluntly, but after twenty years in the business they have a completely different understanding of how things work. You wanna get your point across, you better say it loud, simple, and repetitively. That’s the real world. Get used to it, eggheads.

BACKLOADING OF EXPOSITION – in the last blogpost I talked about my new Get To The Point Rule which is: the quicker you can get through the A and B, the more we’ll let you have all day with the T. You can see this at work in this segment. They have a bunch of factoids to share, but look at where they put them — not in the first act where they would bog everything down. No, they occur about halfway through. That’s what I mean by “backloading.”

STAKES GET RAISED – if you look at The Logline Maker (a 9 part template for crafting an entire story, presented by Dorie Barton in our book “Connection”) you see that step #5 is “The Stakes Get Raised.” You can see that right about the midpoint of the segment. We’ve established that the reef is suffering major problems, BUT here’s what’s worse — the officials aren’t even sounding the alarms about it. What this means structurally is that right about the time the story might be starting to lose momentum they kick it up by raising the stakes. You know how you know to do that? If you have narrative intuition, that’s how.

FINAL SYNTHESIS – the segment ends with the double shot of the core message — that the reef is DYING — spoken by both Charlie Veron, then repeated by Dean Miller. Did they cue Dean to say that bit or did the editor just find it in the interview. I’d guess the former. Then they put the visual lid on the presentation with the final aerial shot pulling away from the reef.

THE NARRATIVE INDEX (BUT/AND RATIO) – here’s a final demonstration of how competent these folks are as storytellers. I have defined The Narrative Index as simply the ratio of the word “But” to “And” for any given text. Some day the know-it-all journalists of the world will open their minds enough to realize how simple and stunningly consistent the patterns are around this index. For now, you’ll just have to use your common sense. Granted it’s not super precise for relatively small amounts of text like this twelve minute segment, but still, the pattern is clear. Have a look:

This is not a fluke. There’s almost no “but’s” in the first act for exactly the reasons I listed above — there shouldn’t be any contradiction in the first act. It’s a place for AGREEMENT. It needs to be free of narrative twists so you can establish the Ordinary World clearly in the viewers mind.

Once the second act begins with the statement of the problem, it’s then time to take us on the whole journey full of twists, turns, and raising of the stakes (“But they aren’t sounding the alarms”).

BOTTOM LINE – The HBO Real Sports team are incredibly gifted at the challenge of creating effective narrative structure. If you doubt this, just watch the stunning story in this same episode they tell about baseball player Rod Carew and his heart transplant. And I mean STUNNING. The stories they find are so powerful, and often have little to do with sports. Their stories are about what interests humans most, which is HUMANS (not science or coral reefs or climate change).

For years I have said the science world could, in theory, produce an equally good program. It would just require one thing — that the producers NOT love science. That is the bane of science programming. Endlessly. The producers always love their science and see humans as inconvenient baggage. The result is content geared for science lovers, not the general public.

And sad to say, given how much I have loved the ocean my entire life, the problem is even worse — much worse — for “ocean lovers” and what they produce.

Here’s my crude outline of the segment, showing these points of structure I’ve mentioned.

FIRST ACT

Great Barrier Reef is paradise.

It provides a religious experience

SIZE – length of east coast US, area of Germany

LARGEST venue – SUPERLATIVE #1

“NOTHING compares to it” – Dean Miller SUPERLATIVE #2

“It’s like a city full of 3-D billboards” (MAKING IT RELATABLE)

ACTIVE JOURNEY – headed to Port Douglas

“Dream like”

“MORE species than anywhere on the planet” – Miller, SUPERLATIVE #3

Gumbel — affirming, adding to superlatives

END OF FIRST ACT – “There’s just one very big problem”

SECOND ACT – the journey begins

THE PROBLEM: Healthy parts like this are getting hard to find

Been around for 25 million years, now DYING (THE MESSAGE)

CAUSE: Fossil fuel burning (but only teased at, start with specifics of bleaching)

IMMEDIATE PROBLEM: Bleaching

Miller: Bleaching means starving (simple language)

Gumbel: Was there one specific moment? (power of storytelling rests in the specifics

Miller: Yes, April, last year — tells of first seeing it

Charlie Veron: We’ve lost HALF

Gumbel: That’s right, half (REPETITION)

Specifics: 30% last year, another 20% this year

SECOND JOURNEY – to view the devastation

“The Godfather of Coral” — SUPERLATIVE #4

“World’s Largest Underwater Graveyard” – SUPERLATIVE #5

BACKLOADING OF EXPOSITION

1 Home to 1/3 of marine life

2 Main source of food for 1/2 billion people

Veron: EVERY coral reef region has been severely hit SUPERLATIVE #6

MORE BACKLOADING OF EXPOSITION

– Great Barrier Reef is great for business

– Centerpiece of Australia’s booming tourism industry

1 2.5 million visitors

2 65,000 jobs

3 6-7 billion dollars/year

STAKES GET RAISED: Officials not sounding alarms

Steve Moon, Tourism Spokesman: The damage is patchy

(to Moon’s credit, Bryant asked, “If you lose the reef do you lose tourism?” He replies absolutely)

THIRD ACT – The real problem is mining industry

#1 Producer of Coal – SUPERLATIVE #7

Veron: Coal industry is the WORST possible thing Australia could do – SUPERLATIVE #8

Matt Kanaban, Minister for Resources of N. Australia: Don’t think coal and environment are at odds

Carmichael Coal Mine will be the BIGGEST coal mine on the planet – SUPERLATIVE #9

Trump Paris Accord

Veron: President of the country that has produce the MOST science – SUPERLATIVE #10

Gumbel: Why are so many supportive of coal?

Veron: Money

Veron: Climate change seems to be off in the future, BUT the truth is the Great Barrier Reef is DYING

Miller The reef is DYING – ITERATION

FINAL VISUAL: Wide aerial shot pulling away