In our ABT Framework course we hit a moment where two of the team members — a marketing expert and a scientist — realized the similarities in the communication dynamics of what they do. Here they match notes on three topics: 1) PERSUASION, 2) CONTROLLING THE NARRATIVE, and 3) THE NARRATIVE SPIRAL (as developed by Park Howell). There is great wisdom for scientists in these parallels.

THE COMMUNICATION OF BUSINESS, THE COMMUNICATION OF SCIENCE — not really that different in the end.

THE SYNERGY SPIRAL

We’ve run the ABT Framework course four times since April. In the second round marine scientist Dr. Dianna Padilla listened to the presentation from Park Howell who is a business/marketing guy, and host of the popular podcast, “The Business of Story.” He has no science background, but she heard things in his presentation that resonated with her years of writing research grant proposals as well as having served a year as a rotator at the National Science Foundation headquarters in Arlington, VA.

They talked a bit further, then I asked them to address these three similarities in communications dynamics for business versus science. Here’s their parallel takes on three aspects of narrative.

1) PERSUASION

We all know that business is about persuading people to buy your product, but grant writing is also about persuading — as in persuading the funding source to fund your project. We can actually use the Dobzhansky Template to say it concisely like this: Nothing in Business and/or Proposal Writing makes sense except in the light of Persuasion.

BUSINESS GUY (Park Howell): Persuasion is everything when it comes to business. Here’s my Dobzhansky Template: Nothing in GROWING A PURPOSE-DRIVEN BRAND makes sense except in the light of PERSUASION. If you can’t connect with and convince your internal, external and partner audiences to buy into your vision and participate in your mission, then you will not make the impact in the world you seek and your organization will suffer.

SCIENTIST (Dr Dianna Padilla): This is where I made my first connection with what Park had to say about business. As in business, the key to a successful scientific research proposal is persuasion. The job of a proposal writer is to persuade critical reviewers and a program director that the work you propose is the best, most exciting, will advance science the furthest, and/or is the key piece of information we need to make important advances. Furthermore, you and your team not only have the skills to get it done, you are in a position to really move things forward, answer important questions, and fulfill the goals and mandates of the granting agency. Just as Park is saying about business, you need to pursued the client (granting agency) to buy into your goals and project.

2) CONTROLLING THE NARRATIVE

BUSINESS GUY (Park Howell): CONTROLLING THE NARRATIVE means tell a true story well, and then supporting it with the facts and figures you need to become THE trusted source. You sell to the heart through telling a story on purpose to get the head to follow. I mean, when was the last time you were bored into buying anything? I use the terms audiences and customers interchangeably because in every audience you are trying to get them to buy into your way of thinking and with every customer, you are trying to sell them something. Both interaction is a transaction. Audiences/customers show up with their own stories; perhaps stories about you, your industry, your competition and their own baggage. Sometimes these stories are true, but mostly they are false because they are made up by your audience from current beliefs built on past experiences. Therefore, if nothing in business makes sense except in the light of persuasion, then you MUST control the narrative. I’ve learned that if you don’t intentionally tell a story, your audience will leave with a story you did not intend. They’ll make something up because you didn’t control the narrative.

SCIENTIST (Dr Dianna Padilla): Again, this is similar to the dynamic for writing of a successful research proposal. You are presenting your narrative, and you need to do your best to keep reviewers following along. But reviewers are scientists, each with their own background, ideas of what is important (their research, of course), and will read your proposal through their personal lens. YOUR JOB is to keep the reviewer following your narrative, and not get distracted or allow them to pull away to their own interests, and wonder why you are not trying to answer another question they find more interesting. With a well crafted narrative, you can pull the reviewer to follow your path of logic, and see that your questions or system are the only ones to follow, and you are proposing something that should be funded. As with business, if you don’t provide a compelling narrative for readers to follow, they will find another path that will not result in success for your proposal.

3) THE NARRATIVE SPIRAL (SEE FIGURE BELOW)

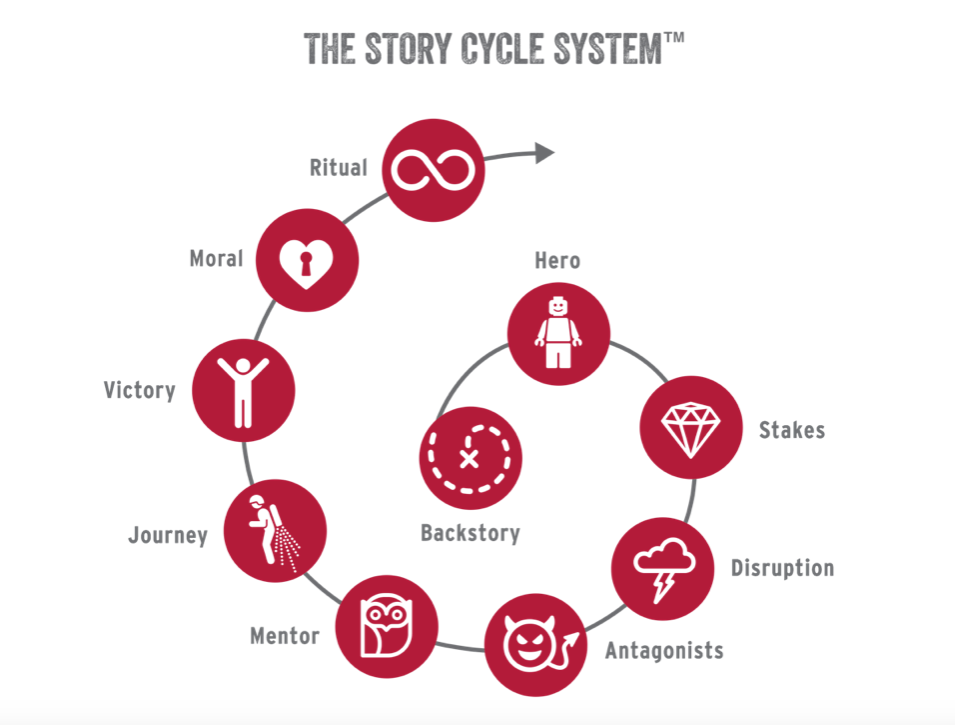

BUSINESS GUY (Park Howell): So here’s how it all comes together. To be persuasive by controlling the narrative, you need a system to organize and guide your communications. This is where I found the Story Cycle System™ narrative spiral to be invaluable to guide long-form communications and presentations. It is inspired by Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey but is mapped to business and intellectual pursuits versus just dramatic storytelling. In my book Brand Bewitchery, I describe the organizational device of the Narrative Spiral. The Story Cycle is distilled from the timeless narrative structure of the ancients, inspired by the story artists of Hollywood, influenced by masters of persuasion, guided by trend spotters, and informed by how the human mind grapples for meaning.”

SCIENTIST (Dr Dianna Padilla): This is where I also see amazing similarities between the path of developing a narrative for business as Park describes it and the writing of scientific research proposals. There are direct parallels. Applying his Narrative Spiral concept to a research proposal, the process begins with the background state of knowledge, putting your proposed work in that context. You lay out how your work will advance knowledge, and what is at stake (if we knew x, then we could….), but we do not know this, some approaches will not get us the answers, etc. Then you use strong narrative to lead the reader to your path of logic on what you are proposing to do and why it will solve those important problems. You then move to the research you want to do, experiments to conduct, data and then how you will interpret the results of your work. The journey ends with how your work will advance science, answer a critical question, or provide essential data that moves science forward. And then, of course, you repeat the whole cycle, only you’re now at the next level up as our knowledge of science continues to spiral upwards.

Story Cycle System™ Narrative Spiral developed by Park Howell in his new book, Brand Bewitchery. It’s Joseph Campbell’s Heroes Journey model, but with a twist — or actually a spiral structure instead of circular. Read his book for the specific details.